Metropole and Periphery in Massachusetts

In "Bridging the urban-rural divide in Mass.,", Lawrence S. DiCara and Matt Waskiewicz note the increasing divides between Massachusetts's urban and rural populations, and propose a few fixes. The piece begins with the unsurprising observation that metro Boston went for Clinton, while Trump carried the rest of the state.

And it’s not just political divisions on the rise -- gaps are widening between urban and rural with regard to educational attainment, inequality of opportunity, and even life expectancy. While the Globe’s and similar analyses suggest one consequence of our geographic divergence, much less attention has been paid to how this divide formed — and more importantly, what we can do about it... Smart, flexible policies that recognize and harness the interdependence between Boston and the rest of Massachusetts will help bridge our urban-rural divide and bring greater prosperity and a more sustainable future for our state and its people.

The authors explain that "automation and corporate offshoring" have eroded paths to the middle class for "families and communities that once relied on manufacturing wages." They propose three fixes: incentivizing large Boston food consumers to buy produce from Massachusetts farms, promoting rural tourism and recreation, and building commuter rail between Springfield and Boston.

Regional inequality is a very big deal. People who live in areas undergoing regional decline have fewer career, educational, and social opportunities. And in larger metropolitan areas like Boston, the incredibly high cost of living erodes the potential of cities to equalize outcomes and improve people's lives. So it's disheartening to see well-meaning authors misunderstand the nature of regional inequality. Especially in Massachusetts, regional inequality is driven by differences among cities, not differences between city and country. In addition, DiCara and Waskiewicz's proposals would reinforce the metropole-periphery relationship -- with its attendant political, social, and economic inequalities -- that Greater Boston has with the rest of the Commonwealth. Rather than hoping that enlightened Bostonians share their bounty with the rest of the state, we should strive for a multipolar Massachusetts, with a number of strong regional, interdependent economies.

What rural decline?

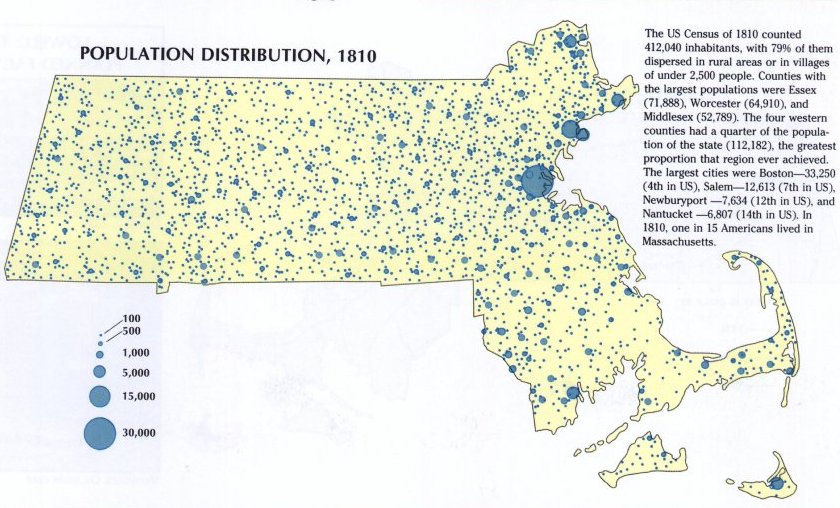

Let's take a look at the historical population patterns in Massachusetts. The following maps1 of the Massachusetts population distribution in 1810, 1860, 1900, 1950, and 1975 come from the "Historical Atlas of Massachusetts," published in 1991. Click to advance:

(I could not find historical population maps which included more recent data; perhaps I'll make some for a later post.)

From 1810 to 1860, the population went from 79% rural to 60% urban - a flip of 81 percentage points! Massachusetts was around 85% urban from 1900 to 1975. Nowadays, it's up to 92% urban. Rural decline, at least relative to urban populations, happened nearly two centuries ago, as the country urbanized and industrialized. In addition, many people who live in rural areas and small towns actually work in nearby small cities -- despite the popular conception of rural areas dominated by agricultural work.2

Rather than being an urban-rural divide, the regional inequality divide in Massachusetts is among urban areas. In the maps above, Greater Boston grows to dominate the metropolitan areas around it, particularly between 1950 and 1975. Today, over 80% of Massachusetts's population lives in Greater Boston. But despite the growth in Greater Boston, the city of Boston actually lost 20% of its population between 1950 and 1975 as urban populations moved to suburbs, and former independent metro areas became satellites and suburbs of Boston.

We see two drivers of inequality due to Massachusetts's growth patterns. First, Boston's growth outpaces other metro areas. Those other areas, like Worcester and Springfield, relied on industrial jobs which have largely dried up. Second, suburbanization hollows out Boston, leading to inequalities between the wealthy suburbs outside Boston and deprived areas in the city itself. But in each case, the difference is between cities, rather than between rural and urban Massachusetts.

Empty trains in empty places

An empty MBTA train car, like the ones that would go between Springfield and Boston (from Miles on the MBTA).

An empty MBTA train car, like the ones that would go between Springfield and Boston (from Miles on the MBTA).

Unfortunately, DiCara and Waskiewicz's proposals would intensify the metropole-periphery relationship between Boston and the rest of Massachusetts. While they are well-meaning and will do some good, these proposals are not appropriate solutions to regional inequality.

The proposal to link Springfield and Boston by commuter rail exemplifies the lazy analysis in the article. I think public transportation is great. But this is an extremely odd proposal for bridging the urban-rural divide. Springfield is not a rural area! It's the second-largest metropolitan area in the state after Greater Boston. 90-minute train service between Springfield and Boston would be quite nice, but it would not do anything for the rural population of the state.

It's interesting that the term used is "commuter rail," rather than, say, "interurban rail," given that it is extremely unlikely anyone commutes from Springfield to Boston. (I did a quick Google search to see if I could find data on how many commuters this rail project would benefit, but all I could find was this Reddit post where a helpful commenter gives some advice to a prospective Springfield-Boston commuter: "Are you dumb? That's a 90 MILE commute. No normal human does that.")

Commuter rail is not a tool that decreases regional inequality; rather, it's a tool that reifies and reinforces regional hierarchy. If Springfield became a bedroom community of Boston (unlikely, since there are better candidates for new suburbs closer to the Hub), Massachusetts would lose a vital independent metropolitan area and gain... another Boston suburb.

There are many vital rail improvements Massachusetts should make, such as the North-South rail link and MBTA electrification. If Springfield had a much larger population and economy, more business and social ties to Boston, and land use policies that favored dense downtown living -- all of which would do a great deal to decrease regional inequality in Massachusetts -- perhaps a Springfield-Boston rail link would make sense. Until then, nope.

DiCara and Waskiewicz's other proposals can similarly be dispensed with pretty easily. Incentivizing in-state agricultural purchases and rural tourism is great. But tourism and agriculture will never be able to make up for the industrial decline that has decimated Massachusetts' small cities. Agriculture is subject to the same mechanization and consolidation forces that led to decreasing factory jobs. While tourism is quite important to the economies of the Berkshires and Cape Cod, it is just one small sector with limited potential for job-creating growth. And as economic development strategies, both policies as developed in the article increase dependence of the periphery on the Hub.

What then must we do?

In the Washington Monthly, Philip Longman argues that the increase in regional inequality in the U.S. is due to specific public policy decisions. In particular, federal antitrust enforcement used to ensure that no company or region was able to unfairly dominate. Regional inequality declined until around 1980, until Chicago School economists convinced policymakers that ensuring low prices for consumer goods is more important than fighting monopoly power -- and local stores fell to chain stores, local companies to multinationals, eroding the economic base of small towns and cities across America.

Though I am sympathetic to Longman's argument, his diagnosis has some holes in it. Regional inequality has been increasing around the world, not just in the U.S. Smaller cities in England and France have declined while London and Paris boom; mega-cities such as Beijing and Lagos have grown in tandem with rural population declines in Nigeria and China.

But whether we grant Longman's argument or not, the idea that regional inequality is linked to larger historical patterns suggests that there isn't much the state can do about regional inequality. We must simply lobby the federal government to rearm against monopolists. While we certainly should push for federal action on regional inequality, there are a number of steps Massachusetts can take to reduce inequality, or at least ameliorate the worst effects.

Here are three proposals for addressing regional inequality in Massachusetts:

1) Invest in health.

As DiCara and Waskiewicz note, rural Massachusetts has worse health outcomes and life expectancy than in Greater Boston. As in other small towns across America, heroine and meth are big problems. Massachusetts should spend more money on health care, drug treatment and rehabilitation. Besides being a basic, necessary social service, health spending can act as an economic catalyst, as hospitals become major regional employers. The California legislature recently introduced a bill to explore universal health care. Massachusetts, long known as a health policy innovator, should follow California's lead.

2) Build more housing.

At least for the time being, Boston is the main economic engine in Massachusetts, but it is incredibly expensive to live there. The state should make lowering the cost of housing in Boston a top priority, both through allowing more private development and by expanding public housing. Bay Staters from outside Boston should be able to move to Boston to take advantage of its economic opportunities, but currently it is prohibitively expensive. Public housing should be built or acquired in Massachusetts's small towns, too. For the elderly in particular, even if a house is affordable, it may be unrealistic to live in a single-family home in context of land-use patterns that require traveling long distances to buy groceries or see a movie.

3) "Right-size" transit.

Rail between Springfield and Boston is probably not a great transit investment for the state, but that doesn't mean that no investments should be made. The state should investigate corridors outside Greater Boston that could be good candidates for higher-capacity transit, such as Fall River/New Bedford, or Northampton/Springfield. Connecticut's CTfastrak is a great example of successful, efficient mass transit between mid-sized cities in New England. (To paraphrase Picasso, great states steal.) In addition, the state should expand dial-a-ride options in rural areas and small cities, particularly for those who can't (or can't afford to) drive.

DiCara and Waskiewicz correctly diagnose Massachusetts as suffering from an acute case of regional inequality. However, they misunderstand the nature of that inequality, and propose fixes that will only reinforce Massachusetts's hierarchy. Instead, we must directly address the decline in material conditions outside major metropolitan areas, and work towards policies that can mitigate the unequal systems that lead to regional hierarchy in the first place.

1 These maps turned out to be less important for my argument than I thought they'd be. But they're still pretty cool so I left them in.

2 "The employment base of a rural town is often dispersed and distant, typically to a larger regional center — for example, a small city — where there are factories, a state hospital, or other major employers." From Economic Growth Issues in Massachusetts Rural Areas and Small Cities by Nancy Goff, a 1994 public policy brief.